What I did in Narnia, and Narnia did to me

My reflections on The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe at 75. Plus sign up for a Narnia @ 75 online book group discussion, 8pm GMT on 30 October

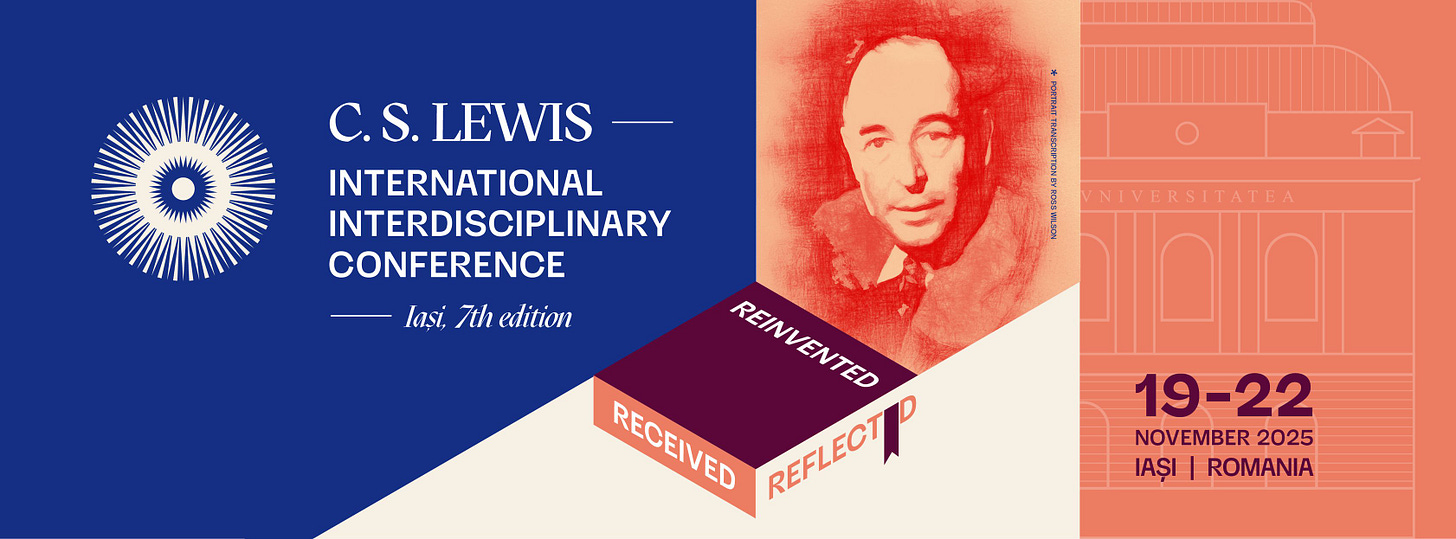

I’m excited that I’ll be off to the C.S. Lewis International Interdisciplinary Conference next month! I also took part in a Discarded Image reading group on YouTube recently, discussing Lewis’s book about the Medieval worldview. I’m also hosting an online Narnia book group soon – register here. Or scroll down for more details of each.

But first, my celebration of 75 years of Narnia!

My adventures in Narnia

Today marks 75 years since the publication of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, published 16th October 1950.

I was only about five years old when I first stepped through the wardrobe into Narnia. Not literally, of course. But when my mum first read The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe to me, something happened to shape my imagination indelibly.

Under Narnia’s spell

I was captured by this amazing world of talking beasts and mythical creatures, by the possibility of as a child stumbling into a magical land and becoming a king there.

I was entranced by the character of Aslan, “not safe, but good”.

I was stirred by the stories, from Aslan’s sacrifice for Edmund in the first book, all the way through to the heroic, helpless last stand of Tirian, Jill and Eustace in The Last Battle, only to be alive again in Aslan’s country: the term time was over, the holidays begun, indeed.

That melancholic sense of fighting, in Tolkien’s words, “the long defeat” of history, combined with fairy-tale, eucatastrophic hope impressed itself on my young mind powerfully.

Longing for Narnia

I longed to visit Narnia for myself. I checked the back of my own wardrobe, looked for hidden portals.

There was one particular branch that came down in my infant school playground in some winds, with a split in two. Pointing downwards to the ground, it made an inverted ‘V’ like a natural archway: just the thing that felt as if it should be one of the ‘chinks and chasms’ that Aslan hinted connected our world to Narnia, that were almost gone but not quite.

I knew Narnia was ‘just’ a story, but as a young Christian, I prayed fervently to God that somehow he would make Narnia real so that I could visit it. I knew from the Bible that God had created this world with a word: if I asked nicely enough, surely God could recreate Narnia based on C. S. Lewis’s words?

He didn’t oblige me, of course. Neither did the trees answer me, or the robins in my garden speak to me, or dwarves or dryads appear amongst the Welsh hills where I grew up, as believable as it seemed that they could be hiding there.

Later, I would encounter Lewis’s ‘argument from desire’, that if I have a desire that nothing in this world can satisfy, it shows I was made for another world. And maybe one day, in the New Creation, in Aslan’s Country, we will indeed get to experience ‘the real Narnia’: not a literal recreation but the source of those desires, where we are restored to perfect harmony with woods and waters, beasts and spirits, and above all God himself. But not now, not yet.

When I was a little older, I started writing my own retelling of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, in which I became part of the story through the power of an enchanted Blue Peter badge. As I grew, I started writing stories of my own that took less direct inspiration from Narnia: tales of magic and other worlds, of good versus evil and of courage and heroism.

Deeper magic

I also began to realise one of the dimensions in which Narnia is ‘bigger on the inside’: the Christian themes and imagery that Lewis embedded in the story.

Some readers have felt short-changed by discovering Aslan is a ‘magic Jesus lion’, and I can sympathise with that feeling. I remember feeling a perhaps analogous sense of disappointment as a kid when I read an article in a newspaper that I read in my local library that pointed out some of the implied Blairite politics of the Harry Potter series – not that I necessarily had a coherent political disagreement with Rowling’s politics, but I felt that somehow the magic and escapism was ‘sullied’ by these real-world concerns.

Of course, by now I’m much more aware of how all fiction is inevitably embedded within philosophical and often political outlooks. But I can understand having some sense of underhandedness when the penny drops about aspects of a story that the author was “up to” without it previously being obvious.

But for me, Lewis’s defence that Aslan is not allegory, but ‘supposal’, a speculation about how God might become incarnate within a world like Narnia, made sense to me as a young Christian with an active imagination and love of speculative fiction.

For me, the flavour of Christianity added “deeper magic”, a grandeur and substance. to the Narnia books; Narnia, in turn, brought to life aspects of the Christian life that might have been difficult or abstract for me to grasp, such as God’s holiness, with the giddy mix wonder and fear that came with meeting Aslan a worthy preparation for grasping the beauty and fullness of awe that come in encountering God.

A baptised imagination

Having encountered a deeply-felt sense of the wild beauty and goodness of God through Narnia helped inoculate me against some of the attacks on Christianity I would encounter growing up.

I read and enjoyed Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials novels though with diminishing pleasure as his atheistic subtext became text, with what seems to me a blundering note of preachiness far worse than any of Lewis’s far more minor crimes against subtlety.

The figure of “The Authority”, the version of God that Pullman rejected as austere, dusty, and tired, bore little resemblance to Aslan, or indeed to Jesus, and so the critique fell short: I didn’t believe in the God that Pullman didn’t believe in either.

And perhaps that’s one of the reasons Pullman objected to Narnia so deeply, for the crime of “baptising the imaginations” of children with stories that might prime young minds to receive the Christian faith as beautiful and true.

A doorway into literature

As I grew older, Narnia became something more: a doorway into myth and literature. I followed Lewis and Tolkien upstream into the worlds of Greek, Roman and Norse mythology, and as I studied literature at university, to Milton, Spenser, Mallory, de Lorris, Dante, Boethius and others.

I loved reading as a child, as I still do, even with my brain at least half-addled by the age of smartphones and social media; I’m sure if it hadn’t been Narnia then other stories would have filled the gap and drawn me in, though my path and my interests would undoubtedly have been different.

But Narnia was my first love, the first children’s novels I read, beyond picture books and simple tales, that first enchanted me.

An enlargement of self

After all, that’s the power of good storytelling: the tale is not only bigger on the inside than the out, like the wardrobe to Narnia or the stable door to Aslan’s country.

But good stories also help make you “bigger on the inside”, inculcating knowledge, curiosity and courage.

It was in Narnia that I learned what it was like to slay a wolf and clean my sword after; to submit to the Lion’s claws as he performed my undragoning; to go cheerfully to a last battle with no hope of victory; to seek after the sweet light of the Utter East.

Handing on to the next generation

And now as a parent, I recently got to experience them in a new way again, reading them aloud to my daughter, who is now eight years old. She is quiet and thoughtful, taking things to heart and keeping her own counsel, so whether they have had the same impact on her as they did on me at her age remains to be seen. But she has heard these stories read to her with love and delight, and our times reading together are precious.

Along the way, many were the times when I had to hold back my tears as I reread them, from the death and rebirth of Aslan, to the singing of Narnia into being, to the end of Narnia and the beginning of the great story that goes on forever.

I hand on Narnia with joy, and hope that a new generation will get at least some measure of the same richness out of them as I did.

And perhaps too it will be a doorway into bigger worlds: those of literature and myth, yes, but also into what Lewis saw as the Great Story, the true myth of Christ born, crucified and risen again.

What does Narnia mean to you? Did it inspire your imagination, and were the Christian themes a highlight or a turn-off for you? Let me know in the comments!

Join me for a 75th Narnia anniversary livestream – Thursday 30th October, 8-9pm GMT

I’m going to try something new! I’ll be running an online book group style chat about The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe in two weeks’ time.

I’m planning to host a livestream to discuss The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe to mark its 75th anniversary. All perspectives welcome, whether critical or celebratory, Christian or from other belief perspectives, as long as you engage respectfully in the discussion.

The discussion will be live-streamed on my Imaginative Discipleship YouTube channel and available publicly afterwards. If you would like to take part in the discussion, or just to register your interest as a viewer, please fill out the form:

Meet me at the C S Lewis International Interdisciplinary Conference in November

I’m excited to have had a paper on childhood, maturity and the Fall in C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia and Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials accepted for this C. S. Lewis conference in Iași, Romania next month — and some creative contributions poetry-wise too! Off to Romania next month for 19-22 November.

Really enjoyed reading your reflections. I loved Narnia since before I could read the books for myself and still love them 40 years later.

Really loved reading this Caleb. We've talked Narnia a bit, but I too loved them. I did not get read them, but encountered them first in my early teens. I adored them and felt annoyed and left out that I hadn't been read them sooner. I continue to revisit Narnia through university and most recently with my own girls.

I also just discovered and read His Dark Materials. I had never heard of them until moving to the UK and studying more about British children's literature. I have so many thoughts about them. Would love to chat about them sometime. And I loved your short thoughts on them here and fully agree.