Charlie Kirk and the importance of conversation

Christianity, politics and depolarisation in an age of political violence

Over the last few days, I’ve been trying to process the awful news of the shooting of Charlie Kirk. I was only peripherally aware of him until now, and while my politics are very different, I pray for his wife, kids and wider family and friends as they come to terms with a shocking loss.

For anyone to be shot for their political beliefs and campaigning is an ugly, evil thing. Each act of political violence further frays the fabric of the West’s rapidly degrading democratic culture. It turns up the temperature in the already overheated culture wars, exacerbating the political climate crisis of deepening polarisation.

But what can we do about it? What kind of imagination do we need to create a better politics, a better conversation?

Quick note: I hadn’t intended to take a summer break from the newsletter, but it turned out that way between juggling my freelance editing work with looking after the kids in the holidays!

I’ve got some new posts underway on my usual themes of stories, culture, imagination and faith, but I felt I needed to comment on the present moment, especially since I am engaged in initiatives that I hope have some small role to play in addressing polarisation.

Faith and political division

I am a Christian, and so Charlie Kirk is a brother in Christ to me, whatever our deep differences of political outlook. There are some points where we overlapped in beliefs, many others where we would have differed profoundly.

The UK and US are quite different political worlds, so I will happily grant that my viewpoint is limited to speak to the details of Kirk’s politics. But I would see a clear difference in his approach to race, immigration, nationalism and other issues to what I would understand a Christian approach to imply. For example, Kirk rejected of empathy as “a made-up, New Age term”.

However, I know that this isn’t as simple a debate as it sounds: Kirk distinguished sympathy from empathy, echoing Joe Rigney’s argument in The Sin of Empathy, and a lot depends on nuanced definitions rather than a simplistic “uncaring anti-empaths vs morally righteous empaths” that it might be tempting to reduce it to. But I would still see Kirk’s terms as ultimately unhelpful and divisive. I discussed this topic on my podcast episode on Imagination and Empathy:

However, while I’ve only seen a little of Kirk’s content but it seems his was genuinely committed to persuasion, debate and engagement. Despite our differences, I can see I would have been able to have a robust and civil discussion with Kirk.

But now, of course, that possibility is closed off by Kirk’s murder. Dialogue is shut down in favour of violence, the ultimate “shut up!”

As I write, the motives of Tyler Robinson, the alleged shooter are disputed: it’s not clear yet whether he may have been motivated by farther-right extremism, or because of objecting to Kirk from a left-progressive viewpoint, as people try to interpret the memes he referred to and assess claims he was in a relationship with a transgender roommate.

Whatever the full story turns out to be, it seems that he was “very online”, and this likely played a role in some form of radicalisation. While we don’t know the motives and psychology, it seems to me the deep polarisation in US politics and Western culture more widely must have contributed to creating a climate where this kind of evil could seem plausible and attractive to a troubled young man.

The problem of polarisation

There are polarisation dynamics at play that emerge both from left and right wing, and also from the perverse incentives of our media ecosystem and online algorithms to drive engagement at all costs.

Social media prioritises the loudest, most extreme voices, because they provoke more reaction, more clicks, more revenue. Tech companies optimise for addiction, sending people down dark rabbit holes of extreme content. Tech journalist Charles Arthur calls it “Social Warming” by analogy with “Global Warming” — but how far can we turn up the temperature before peaceful democratic debate and politics become impossible?

The UK is seeing a turn away from established parties and institutions and towards the populist right, much as the US saw with Trump. We can see this shift in populist party Reform’s surge ahead in the polls, and in the large demonstration in London this weekend.

The temptation for the left and for traditional institutions is to increase the moral disapproval, the fact-checking, the finger-wagging. Unfortunately this tends to be counter-productive. Suppressing discussion of controversial issues just makes them fester. What then can be done?

No easy answers

There are no easy answers to our political problems: there are difficult economic and social challenges concerning growth, population, immigration, and a crisis not just of deep disagreement over what should be done, but also a crisis of confidence in the ability of government to do anything effectively.

Lightning-rod issues like policy around trans are to a significant degree zero-sum: when it comes to bathrooms, women’s sport, self-identification and so on, you have some pretty binary policy choices to make.

Conversation by itself can’t solve our problems. But it perhaps creates the conditions in which solutions can be found.

The necessity of conversation

If there are solutions to be found, then I believe that we can only reach them by turning down the temperature, by depolarising debates so that people of radically different beliefs can actually sit down and talk to one another, human being to human being.

Online life can’t bear the weight of that (at least without radically defanging the algorithms): meaningful dialogue needs in-person, embodied human interaction. Dialogue needs spaces where people can meet with the assumption that the person on the other side of the debate has intelligible, very likely well-meaning, motivations and reasons for their position. You might have something to learn from them, and at the very least, they are a human being who deserves the dignity of being heard, and being responded to with reason and empathy, even if their views are profoundly erroneous, harmful and offensive.

How I’m doing this in my community

I hope it’s not inappropriate for me to discuss these – I don’t want to bandwagon on someone’s death just to plug events I’m running! But I do think it’s important to discuss what building conversation and community can look like in action, so I’m going to talk about what I’m up to.

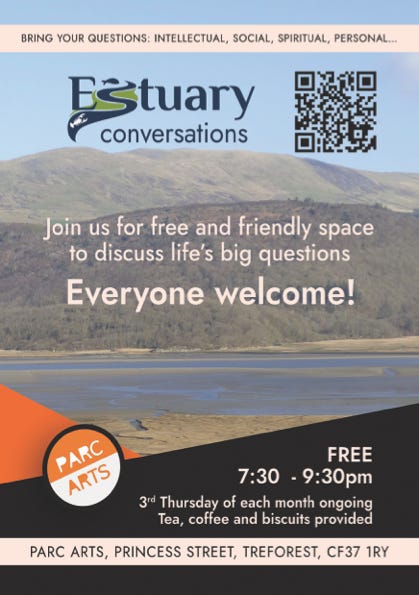

Estuary Conversations, Treforest

The need for conversation is why I’m so invested in running the Estuary Protocol, a format for conversations designed to bring people together across difference. I’ve been running it monthly in Treforest as a free and friendly space, and while numbers have been small, the quality of conversation has been high.

We need places to practice the art of conversation, of being able to engage well with contrary viewpoints, listening to, learning from, and loving our neighbours. I’ve found Estuary fascinating and stretching as I’ve engaged with different people and their views.

To find out more about the Estuary Protocol and network of groups, visit estuaryhub.com.

The Table, Cardiff

I’m also helping Urban Crofters, a church in Cardiff, with a similar initiative called The Table, which aims to create space for people to connect and talk more deeply (specifically over food, which is an excellent bonus!)

Aimed specifically at 18s to 30s, it’s another version of creating space for community and conversation. If you’re in the right place and age bracket, you can sign up on Meetup.com.

Churches and depolarisation

I also believe depolarisation is something that churches should be modelling. Christians should be united by faith in Christ, across political divides. We should be committed to loving both our neighbours and loving our enemies — and as G. K. Chesterton observed, often these are the same people!

But avoiding division in the church, and between the church and its neighbours, takes effort, especially when there are unhealthy extremes and distortions across the political spectrum that Christian discipleship needs to address. A naive “both sides”-ism will just annoy everyone.

A good starting point is for church leaders to teach how the church’s loyalty to the Gospel is higher than any political commitments, and to take care not to stereotype or demonise other viewpoints, whether that’s “the crazy religious right” or “the godless woke leftists” or whoever it is that you are tempted to despise.

The antidote to social media?

In-person, intentional conversation is in many ways the opposite of Twitter/X.

Conversation is long-form, not careless ragebait.

Conversation puts you across the table from the person who you disagree with, rather than reducing them to an enemy digital avatar within the massively-multiplayer online game that is social media.

Conversation is slow and requires focused attention, rather than the fast-paced, ADHD nature of our reels and feeds and notifications.

Each conversation only makes a small difference. But it does make a difference.

The more meaningful conversations and connections we can make, the more we can perhaps slowly, incrementally, painfully, turn down the heat on our cultural divides, so that our communities can flourish.

What do you think facilitating meaningful conversation across divides can and can’t achieve?

How are you — or could you — contribute to depolarising our cultural divides in your community?

Let me know in the comments below!

I was thinking about this just yesterday while reading the chapter on “Social Morality” in C.S. Lewis’ Mere Christianity - it feels incredibly up-to-date and relevant for exactly these issues.

Charlie Kirk was seldom, if ever engaging in real conversations in his "debates" with mostly naive not at all sophisticated under-graduates at various universities.

Check out the posting titled Stop the Bullshit on Nils Gilman's Small Precautions substack website.